Night Diving in the Bay of Ranobe

In this volunteer blog, Research Assistant Abby Rogerson describes her memorable experience of night diving in the Bay of Ranobe, in what marked her final dive with us.

“I’m always weary of building up lasts. I need no culminating spectacle to seal an experience, and I find that reflections of my past are more often marked by seemingly trivial occurrences that elucidate a time’s importance. Perhaps this attitude is subconsciously built on a foundation of self-preservation—an indifference towards great endings ensures disappointment will not ensue.

My final dive at Reef Doctor was on a calm Friday night at Rose Garden Marine Protected Area. Rather than my interest waning as I became more acquainted with this reef—its resident species, their behaviours and habitats, the geography of the reef perimeter—I’ve become more attached. Familiarity is a settling feeling as a person uprooted from the subtle details that make one feel at home. Despite my reservations about lasts, the prospect of seeing this place in a different light is exciting, akin to visiting a beloved spot with a new companion—the draw remains unchanged, but details are amplified and refracted through a new perspective.

As we make our way offshore, I look back on the once homogenous coastline, which is now distinguished by time spent and knowledge gained. The dottings of dull green-grey trees are now Euphorbia; the faded red bungalows tucked in the dunes are remnants of the dilapidated Mangily Hotel; the dense stand of pines mark entry into Ifaty. Walks along this beach are differentiated by conversations on the phone with missed loved ones, by slow afternoons spent inspecting tide pools, by disjointed French conversations had with children met on my way.

We tie up to a buoy as the sun dips below the horizon. Flicking on our flashlights, we descend down the algae-laden anchor line. The artificial light illuminates particulates drifting in the water column, and I avert my eyes from the cloudy beams. The ensuing clarity is stark; I’m struck that a medium that exerts such resistance is as invisible as air.

Dusk seamlessly merges into dark. Fifteen feet above, I see the moon’s image stretched across the meeting of mediums and elongated into a rippling spectrum of color. With the moon’s light above and the presence of five others around me, I think about a conversation with my mom in which she said night diving must be unnerving. Although I understand the sentiment, the idea of being frightened in this moment seems irrational. To get a sense of this unnerved feeling, I let the others pass by and turn to see the darkness. My mind drifts to the possibility of being solitary in this blackness, and a pang in my stomach urges me to abandon this curiosity.

By night, short-spined urchins roam freely. Untethered from their daytime congregations, they shuffle singly across the substrate and continue their ramblings up the walls of massive coral bommies. Tiny red fish shimmy amongst their spines and reaching tentacles. Constantly I realise how little I know about the inhabitants of this ecosystem, and I wonder if these hitchhikers are parasites or partners in a welcome symbiosis. Three-spot dascyllus have also shed any semblance of shyness. By day, they nip our fingers to defend the eggs they’ve laid upon the coral nursery’s rebar as we scrape algae off its frame. Now, these small, drab grey fish do not dart away like other species as we pass by; rather, they flare their dorsal spines to the alert. Their prevalence and apathetic disposition begs me to label them the squirrels of the reef.

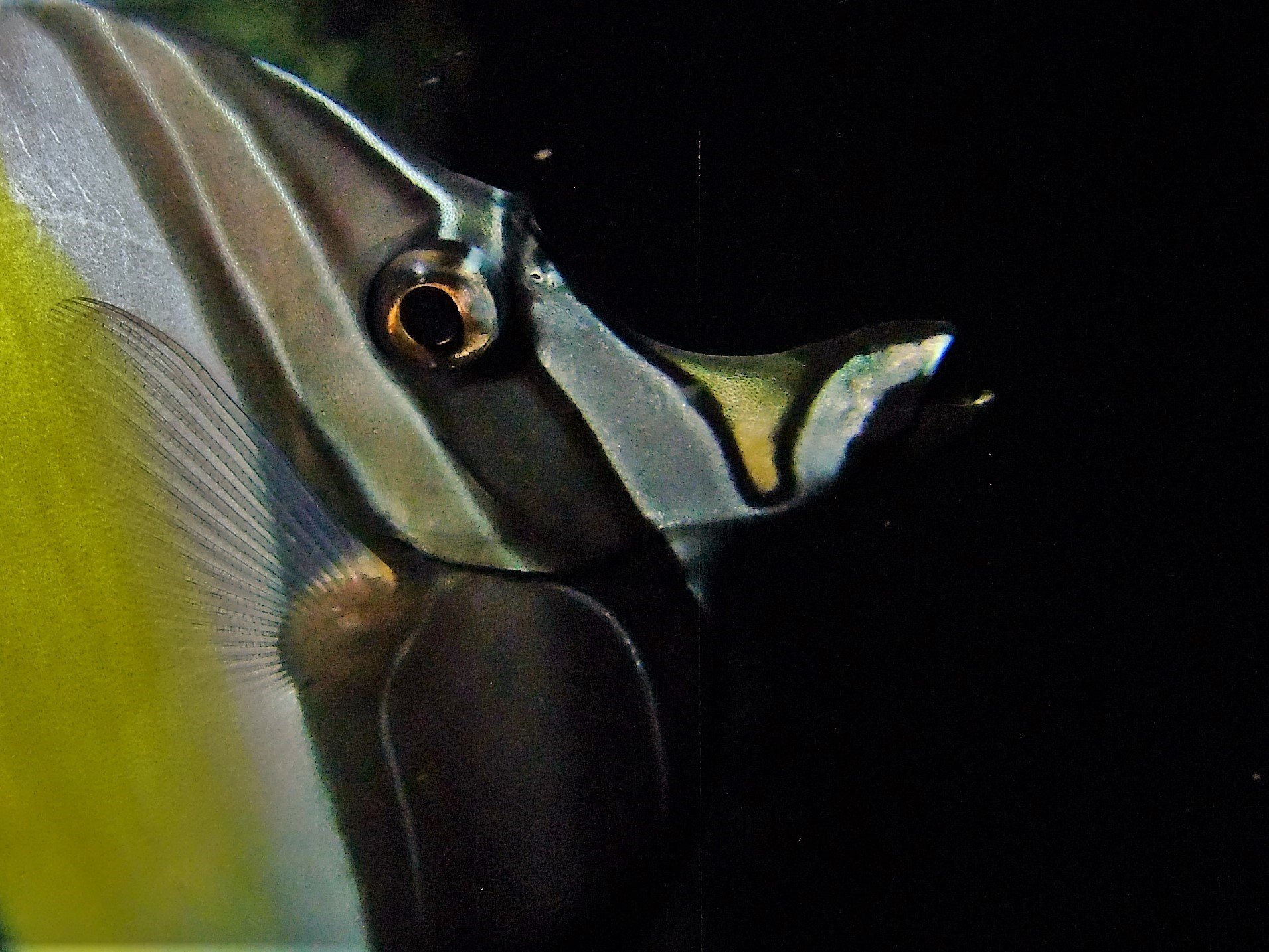

A circling beam ahead catches my attention. My eyes scan the matrix of tan and brown textures and catch the domed form of a cuttlefish—the first I’ve ever seen. Although they are capable of hypnotizing color displays, this one relies on a mottled appearance to keep it disguised among the rubble. A waving flap skirts its squid-like body, which allows it to hover slightly above the seafloor. I reluctantly move on, now distrustful that the broken shards of algae-encrusted coral are as they seem. My suspicion is warranted. An octopus’s bulbous head gives away its camouflage; it is not angular enough to blend into the surrounding mess of coral fragments. As we crowd around, it slithers its tentacles more tightly underneath its body. Its obvious tenseness makes me certain it will flee once free from our attention. Just as my fins pass out of its radius, it launches itself away with a swift extension of its tentacles into the safety of darkness.

Gradually, a faint crackling noise becomes loud enough to catch my attention. Typically, my breath is the only noticeable sound while diving, and it tends to fade from consciousness just as the feeling of breath does. Upon becoming conscious of sound again, I fixate on the mechanical sound of air travelling through my regulator and the purge of bubbles as I exhale. I wonder about the source of the crackling and if the others notice it as well. Although we dive together, each of us has isolated experiences defined by thoughts that cannot be shared, questions that remain unasked, and curiosities that disappear before being pointed out. Our spheres of awareness are separate and overlapping in unknown ways.

This inability to express amazement and confusion is readily relieved upon surfacing. Our hanging flashlights illuminate the water a pool blue as we bob on the surface, breaking the night’s silence with our exclamations and questions. Hypotheses for the source of the crackling are pitched, and descriptions of unknown species discussed. To me, it seems my indifference towards a memorable last dive was met with a barrage of novelty, as if to disprove that this ocean and its many ecosystems could ever cease to be novel.”

Photo credits: Abby Rogerson & Neil Davison